By DOUG BLACKBURN | Tallahassee Democrat

2009-12-22 21:19:39

Dean Falk

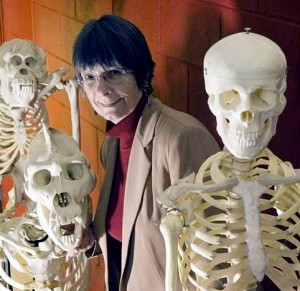

TALLAHASSEE — Dean Falk has a knack for making the past seem incredibly current.

A paleontologist in Florida State University’s anthropology department, Falk has been among the forefront of scientists examining Hobbits, the name given to a species whose remains were first discovered five years ago on an island near Indonesia.

Her work — along with that of others studying the hobbit fossils — has challenged our accepted understanding of human evolution.

Falk, however, is also an accomplished multitasker. During the past two years she has re-examined Albert Einstein’s brain, using photographs of the fascinating genius’ gray matter to determine that the physical attributes of Einstein’s brain may explain his unique gifts.

Her paper, published in May in the academic journal Frontiers in Evolutionary Neuroscience, was one of the top 100 stories of 2009, according to Discover magazine.

Take that, Indiana Jones.

Falk, at FSU since 2001, said she was inspired to study Einstein’s brain after reading an article about functional imaging and the connections between musicians and their brains. String players in particular are found to have a dramatic “knob” on their brain that scientists believe is related to their dexterity, the article said.

Falk, familiar with Einstein’s lifelong love of the violin, had an Aha! moment.

“There it was screaming on his brain,” she said. “It has not been observed because back when his brain was examined, we didn’t know about this.”

While not quite 55 years old — Einstein, referred to by many as the person of the century, was 76 when he died April 13, 1955 — the brain responsible for the theory of relativity has become the stuff of scientific lore, a lost ark of sorts for neurologists and anthropologists. Einstein’s hospital records and autopsy report vanished without a trace, while his brain was removed and cut into 240 blocks, of which 12 sets of microscopic slides were made.

It was those slides which Falk used for examination of Einstein’s brain.

“It’s hard-core science, but it captures the public imagination because it’s Einstein,” Falk said. “Because it’s such an important brain, I thought I would do this basic work and use these photographs to study it from different angles.”

Falk’s work has other Einstein observers taking notice. Fred Lepore, a professor of neurology at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in Brunswick, N.J., said Falk has broken new ground with her Einstein research.

“It’s a very interesting finding in a very controversial area,” Lepore said. “Dean is a crackerjack cortical morphologist.

“She can look at the surface of the brain and the skulls of hominids and make certain surmises. Dean came up with some very persuasive observations. You don’t get that skill-set without knowing a lot of neuro-anatomy.”

Falk also studies language origins. Her book, “Finding Our Tongues: Mothers, Infants and the Origins of Language” (Perseus Basic Books), was published earlier this year.

“Dean is an incredibly driven and inquisitive scientist,” said Charles Hildebolt, a professor at Washington University in St. Louis. “She has devoted her life to studying brain evolution and dealing with the small sample sizes of specimens in the fossil record.

“There has been more than one occasion when she has pointed out to me and colleagues features of fossils that appeared incredibly subtle until we measured the features and created images of the features — at which point it seemed incredible to us that we nor anyone else had noticed what Dean had observed.”

Falk maintains that what we don’t know far outweighs what we do, and that her fields are changing rapidly. Her goal is to keep doing research, making connections while staying connected.

“I’m contributing to a written record for future scientists,” Falk said.