http://www.thespanner.net/

Issue 0008

©2013 Spannerworks, published at 67 Dean Street, London W1D 4QH

International Edition

How the Human Got Her Words

Dean Falk (with apologies to Rudyard Kipling)

This, O my Best Beloved, is a tale that tells how people got their first words. Once upon a most early time—over three million years ago—all people lived in Africa and were speechless. They had not invented words, you see, because all of their time was spent perfecting the art of walking on two rather than four legs, which was a new and better way of getting around. Despite its advantages, walking upright was challenging and required many calories, which stimulated the men to improve their hunting skills. Meat became plentiful and, over time, provided protein and fat that helped the brains of our ancestors become larger—and smarter. Mother Nature saw that it was good and decided that even newborns should have big brains. This created an unfortunate problem for their mothers, however. Giving birth to large-headed infants became excruciatingly painful and, in some cases, impossible. Many women and babies died in childbirth. Only the tiniest and most helpless infants survived. These newborns were so helpless, in fact, that they never developed the ability to cling day and night to their mothers the way that monkey and ape babies do.Because their babies could not remain attached to them, mothers began carrying them everywhere in their arms. This made it difficult to climb trees, dig up tubers, collect water, and pick fruit. Baby slings had not yet been invented (but that is another tale), so what was a poor prehistoric mother to do when she needed to fix dinner—or her hair? Like contemporary mums, prehistoric mothers who wanted to complete their chores had no choice but to put their babies down next to them. Similar to modern babies, our ancestors’ infants expressed displeasure at these temporary separations by fussing and crying. Because automatic rockers, musical mobiles, and other kinds of pacifiers were things of the future, complaining babies were easy pickings for hungry predators. The lucky ones who escaped this fate had mothers who developed methods for soothing and hushing them by making pleasant melodic sounds.

Monkey and ape mothers do not make pleasing sounds toward their offspring, but contemporary people all over the world have inherited this practice from early humans. Modern forms of baby appeasement have added something to this prehistoric invention, however—words. Baby talk (also called motherese) not only soothes infants, it helps them learn speech sounds and where one word ends and another begins. Baby talk also helps older infants produce words and shows them how to string them together into meaningful sentences.

But I am getting ahead of our tale, my Best Beloved. When prehistoric mums first began putting their babies down, they and their infants started gazing directly into each other’s eyes and using facial expressions and “ga-ga-goo-goos” to communicate. Thus began the earliest mutual give-and-take vocal expressions among our ancestors. This paved the evolutionary path for the eventual emergence of the first words. But what were those words, and how did they emerge? Because the time machine is a thing of the future, we cannot be sure. Nonetheless, scholars have long pondered this mystery and made various suggestions. Perhaps the first words imitated sounds from animals (“moo,” “bow-wow”) or nature (“crash,” “boom”). Maybe the earliest prehistoric vocabularies included instructive words like “yuk” (short for “don’t put that garbage in your mouth) or “num num” (“eat up, this is good”). Words for “mama” and “baby” were probably among the earliest invented, as perhaps were names for foods and animals and proper names for people. Once the prehistoric light bulb was turned on by mothers and their infants, the creation of names and, eventually, other kinds of words began in earnest. Maturing infants shared and modified their words in play groups, and took their expanding vocabularies back to their mothers. The men, who spent much of their time out-and-about, learned words when they bought home meat. This system for inventing and sharing words was so good that even some modern monkeys who live in Japan use it to invent cultural practices such as washing sweet potatoes, and deaf children in Nicaragua recently used the same technique to invent and spread an entire sign language. Nevertheless, difficult as it may be to believe, this tale is sometimes viewed cynically by certain (frequently male) academics. But keep in mind, my Best Beloved, that it was so—just so—a long time.

About Finding Our Tongues

Scientists have long theorized that abstract, symbolic thinking evolved to help humans negotiate such classically male activities as hunting, tool making, and warfare, and eventually developed into spoken language. In Finding Our Tongues, Dean Falk overturns this established idea, offering a daring new theory that springs from a simple observation: parents all over the world, in all cultures, talk to infants by using baby talk or ”motherese.”

Falk shows how motherese developed as a way of reassuring babies when mothers had to put them down in order to do work. The melodic vocalizations of early Motherese not only provided the basis of language but also contributed to the growth of music and art. Combining cutting-edge neuroscience with classic anthropology, Falk offers a potent challenge to conventional wisdom about the emergence of human language.

From the Book’s Preface

How language began is a deeply challenging question–intellectually, philosophically, and emotionally. Obviously, there is something about the subject of human origins, intelligence, and our uniqueness as a species that arouses strong opinions, and this can be seen in the polarized questions asked today: Did language begin millions of years ago and evolve slowly, or did it originate much more recently and abruptly? Was the first language (protolanguage) derived from the animal calls of our earliest ancestors, or from gestures? Did language evolve primarily for thought, or was it always used for social communication? And what is the relationship between language and the development of music?

Conflicting theories abound. I believe, however, that most researchers have been looking for the beginnings of language at the wrong point in time—they focus on the recent evolution of Homo sapiens, in the last 200,000 years—and thus have missed a crucial part of the puzzle. This book will take a longer view. The key to understanding the origins of language does not lie after the development of protolanguage, some 2 million years ago, but before—in the mysterious transition between our early ancestors’ divergence from other primates, 5 to 7 million years ago, and protolanguage’s first appearance.

More importantly, many researchers have missed clues about the emergence of language that appear every day in modern infants and toddlers. While infants are learning to speak, parents talk to them in a special way–known as baby talk, musical speech, or motherese. Some linguists have argued that motherese is not universal, but I’ll show that motherese exists in all societies, sometimes in disguised forms tailored to various cultural taboos and practices.

One reason we’ve misunderstood the role of motherese in the development of language may have to do with assumptions about gender. Since at least the time of Darwin, men have been viewed as prime evolutionary movers because of their hypothetical focus on hunting, tool production, and warfare. More recently, women have also become celebrated as evolutionary movers because of their roles in gathering food and helping daughters raise offspring. Still, despite ongoing intense interest in language origins, there has been little focus on how motherese first emerged. This book shows exactly how motherese continues to help babies all over the world learn language, from the moment they are born until they are walking, talking toddlers–and what such observations can tell us about the emergence of language among our species.

From the fossil record of our ancestors to the most recent findings about child development, I’ll draw a completely new picture of the origins of language. Fossils show that an evolutionary dilemma arose when our ancestors began walking on two legs. The narrowing of birth canals associated with upright walking made giving birth excruciating and dangerous. As so often happens, this dire situation was solved by an evolutionary balancing act: only the smaller, less-developed infants (and their mothers) survived the ordeals of birth. Because of their physical immaturity, these newborns lacked the ability to cling unsupported to their mothers, a skill monkey and ape infants very quickly develop. Before the invention of baby slings, women would have had little choice but to carry their helpless babies on their hips or in their arms. More important, they would have been forced to put their infants down as they gathered food.

When separated from their mothers, no doubt the babies fussed, as they do today, and busy prehistoric moms would have tried to soothe them. These mother-infant interactions were the first domino in the sequence of events that led to our ancestors’ earliest words and, later, the emergence of protolanguage.

Motherese may have nudged our young ancestors in other fascinating ways. Just as there are conflicting ideas regarding language origins, experts are also divided on when, how, and why music came about, and whether or not it had any evolutionary purpose. Some, like Steven Pinker, believe that music represents an entertaining but otherwise useless spin-off (“auditory cheesecake”) from neurological machinery that evolved for different purposes. Other researchers reject the idea that music evolved from speech in favor of the reverse notion, as Charles Darwin reasoned long ago. One thing is for sure: babies everywhere are extraordinarily musical, so it is not surprising that people sing lullabies and playsongs to them throughout the world. As I will explain, I believe that full-blown music and language evolved in lockstep with each other over millions of years of evolution as the musical and linguistic sides of the brain (right and left, respectively), slowly became larger and better at processing complex sounds.

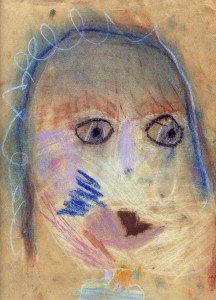

Gesture may also have played a role, not only in the evolution of language but in the emergence of art. Modern children’s artistic development parallels the startlingly early emergence and subsequent development of hominins’ artistic expressions across the archaeological record. Like music, drawings and paintings seem to have emerged much longer ago than many researchers believe.

Certain mental processes, such as the ability to synthesize data, also develop as babies grow and contribute to the flowering of their verbal, musical, and artistic skills. Similar abilities must have evolved as our ancestors became linguistic, creative beings, and we’ll see how changes in the brain facilitated the process.

This book draws heavily on things that parents of small children see, hear, and do every day. These observations suggest that infants must have been of key importance during the extraordinary evolution of our species. Had Mother Nature not favored smaller, less-developed babies because of the terrible hardship of giving birth to bigger ones, our ancestors would never have invented motherese. And without motherese, we would have no dance or literature, no Mozart, Mona Lisa, or E=MC2. We would not have books with which to contemplate the mystery of our origins. In fact, we would not have developed into humans as we know ourselves today. But as we’ll see, Mother Nature did favor helpless little babies, and the trials they faced radically affected their interactions with their mothers. The rest, as they say, is prehistory.